InAppBrowser-Escaper

A lightweight TypeScript library that helps users escape from in-app browsers (Instagram, Facebook, Telegram, etc) to their default browser for a better browsing experience.

Demo: https://jhrun.com/develop/inappescaper/demo.html

Github: https://github.com/jeonghunn/InAppBrowser-Escaper

NPM: https://www.npmjs.com/package/@jhrunning/inappbrowserescaper

License: This project is licensed under the MIT License

Key Features

- Zero Dependencies: Lightweight with no external dependencies

- TypeScript Support: Fully typed with comprehensive TypeScript definitions

- Framework Agnostic: Works with React, Angular or vanilla Javascript

- Mobile Optimized: Specifically designed for mobile in-app browsers

- Customizable UI: Flexible escape modal with customizable styling

- Multiple Strategies: Auto-redirect, modal display, or manual trigger options

- Comprehensive Detection: Detects popular in-app browsers

Supported In-App Browsers

- Instagram (iOS ✅, Android ✅)

- Facebook (iOS ✅, Android ✅)

- Facebook Messanger (iOS ❌, Android ✅)

- Telegram (iOS ✅, Android ✅)

- Snapchat (iOS ❌, Android ❌)

- LinkedIn (iOS ✅, Android ❌)

- Line (iOS ✅, Android ✅)

- KakaoTalk (iOS ✅, Android ✅)

- Safari In App – SFSafariViewController (iPhone ✅, iPad ❌)

- Chrome Custom Tab (Android ❌)

*This information is based on v1.0.0 (November 2025) and may not be accurate depending on the app and OS versions.

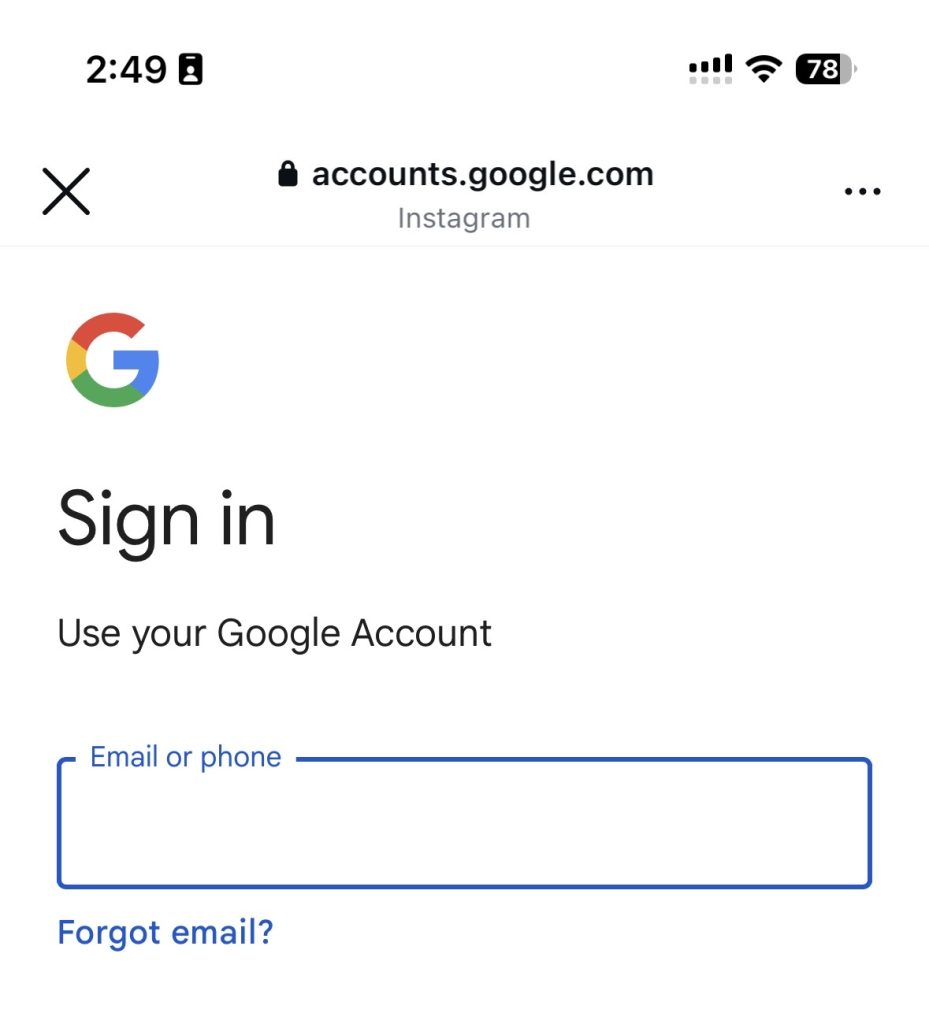

The Problem: That Awkward Moment When You’re Not in a Real Browser

We’ve all been there, You’re scrolling through your favorite social media app, you tap on an interesting link to a youtube video or an article, and suddenly you are on a webpage that just feels… off.

You are logged out for a website you already signed in, You decide to buy something, but your saved payment information is missing. You want to keep the tab open for later, but there’s no way to do that. Why? Because you’re not in regular browser such as Chrome, Safari and so on.

You’re in a stripped-down, in-app browser that the social media app has trapped you in. This is by design. They want to keep you inside their ecosystem and collect data on your browsing habits.

As developers, we spend countless hours building smooth, feature-rich web applications. We optimize our PWAs and ensure our sites are responsive and accessible. But the moment a user clicks from apps such as instagram, facebook, or another app, that carefully crafted experience is thrown into a cage called in-app browser.

This sometimes gives us headaches since these embedded webviews open lack the features and stability of default browsers. Worse,

these embedded webviews often break features or behave unpredictably, even when they use the same underlying engine (like Chromium or WebKit) as the real browser.

A Simple, One-Line Escape Hatch

This is a problem I’ve faced in my own projects, and i wanted a simple, robust, and frame-agnostic solution that could be applied to multiple projects. That’s why i built InAppBrowserEscaper.

InAppBrowserEscaper is a lightweight, zero-dependency TypeScript Library designed to do one thing perfectly: Give your users a clear and easy way to escape the in-app browser and open your website in their default browser where it belongs.

With a single line of code, you can detect the in-app environment and prompt the user to switch.

import InAppBrowserEscaper, { InAppBrowserDetector } from 'inappbrowserescaper';

// Check if the user is in an in-app browser

if (InAppBrowserDetector.isInAppBrowser()) {

// If so, trigger the escape hatch!

InAppBrowserEscaper.escape();

}This simple call automatically handles the detection logic and presents way that guides users to freedom.

For more information on its usage, check out the README page on Github.

Under the hood: The Art of Browser Detection

One of core challenges of InAppBrowserEscaper was reliability detecting which in-app browser a user is in. It’s not as simple as checking a single property. Each app has its unique fingerprints.

Example 1: User-Agent Detection

For example, to detect Instagram, I had to analyze its User-Agent on both iOS and Android. Instagram adds its app name to user-agent.

private static readonly IN_APP_PATTERNS = {

instagram: /instagram/i,

facebook: /FBAN|FBAV|FB_IAB/i,

linkedin: /LinkedInApp/i,

kakaotalk: /KAKAOTALK/i,

};Example 2: Beyond the User-Agent (SFSafariViewController)

While the User-Agent string is the primary tool for detection, some environments are more subtle. A great example is SFSafariViewController on iOS. This is a special in-app browser that looks and feels almost exactly like the real Safari, but with some key limitations.

Because its User-Agent is often identical to the main Safari browser, we can’t rely on our usual detection methods. Instead, we have to infer its presence by checking for specific API availability. SFSafariViewController runs in a more restricted context and doesn’t expose all the standard Safari browser APIs.

// A trick to detect SFSafariViewController

// The real Safari has a 'window.safari' object, but SFSafariViewController does not.

// However, both are based on WebKit.

if (typeof (window as any).safari === 'undefined' &&

typeof (window as any).webkit !== 'undefined') {

// We are likely in a restricted WebKit view like SFSafariViewController

return true;

}This kind of techniques, detecting an environment by its capabilities rather than its name, is a powerful pattern. It allows InAppBrowserEscaper to handle tricky edge cases and provide a more reliable experience for users, even when the browser is trying to hide true identity.

Under the hood: The Escape Plan

Detecting an in-app browser is only half of battle. Helping the user escape is the real challenge. Most in-app browsers intentionally make it difficult to leave the app, as their goal is to keep users within their ecosystem. A simple window.location.href` is often ignored or blocked.

To solve this, InAppBrowserEscaper employs a multi-layered strategy, ensuring the highest chance of a successful exodus.

1. Universal Fallbacks: A Barrage of Attempts

The library attempts a series of universal methods that work across a number of environments. It rapidly fires these off, hoping one will break through the in-app browser’s restrictions. For instance:

window.open(url, '_black'): The classic open in a new tab command. While often blocked, It’s the first and simplest attempt.- Dynamic Anchor Clicks: A more robust method involves programmatically creating invisible

<a>tag in the DOM with thetarget='_blankattribute and simulating a user click on it. - Form Submission: In some locked-down environments, the only way to trigger a top-level navigation is through a form submission. The library can create a temporary

<form>element that targets new window (_blank) and programmatically submits it.

These universal methods form the baseline, but the real power comes from platform-specific escape hatches.

2. Platform-Specific Deep Links: The Secret Passages

When the universal methods fail, InAppBrowserEscaper uses its knowledge of the operating system to try and trigger the default browser directly using special URL schemes.

This is like knowing a secret password to open a locked door.

For Androids (Intent-based URLs):

Most Android in-app browsers will respond to a specially crafted intent URL. This URL scheme tells the Android OS, “This link is not for the current app”. It’s an instruction to the system itself.

By wrapping the desired URL in an intent, we can explicitly ask Android to open it in the default browser.

Example:

intent://${url.replace(/^https?:\/\//, '')}#Intent;scheme=https;action=android.intent.action.VIEW;category=android.intent.category.BROWSABLE;S.browser_fallback_url=${encodeURIComponent(url)};end`For iOS (Custom Schemes):

iOS has a similar concept. By utilizing a scheme x-safari-https, it opens webpage directly on safari.

x-safari-https://google.comBy combining these universal and platform-specific strategies, InAppBrowserEscaper provides a layered and robust escape plan tailored to the specific environment to user is trapped in, maximizing the chance of a successful escape to a better browsing experience.

Leave a Reply